3-axis CNC machines might seem a bit limited when compared to their more complex brethren with a greater number of controls and axes. However, that doesn’t mean a 3-axis machine is obsolete. They are very good for hammering out significant numbers of base parts that don’t necessarily need to be highly polished or delicate and are oftentimes made of much harder material that takes far more durable tooling to work. That said, once angle heads are included in the mix, greater capabilities come into play for 3-axis machines that weren’t possible before, including a greater span of milling and drill work that might not have been possible previously.

Part of the challenge with a 3-axis machine was the fact that the target material kept having to be re-positioned for additional work than just approaching the shaping from 3 angles only. That would then require additional setups, programming, work and repeating the same all over again for a different position. However, by including the ability of an angle head to work from a different position entirely, the same setup can be applied with greater effect. Angle heads provide an exponential widening of scope in terms of what’s possible with a 3-axis machine, yet at the same time there’s no significant increase in work time and there’s definitely no additional setups and programming that have to be implemented.

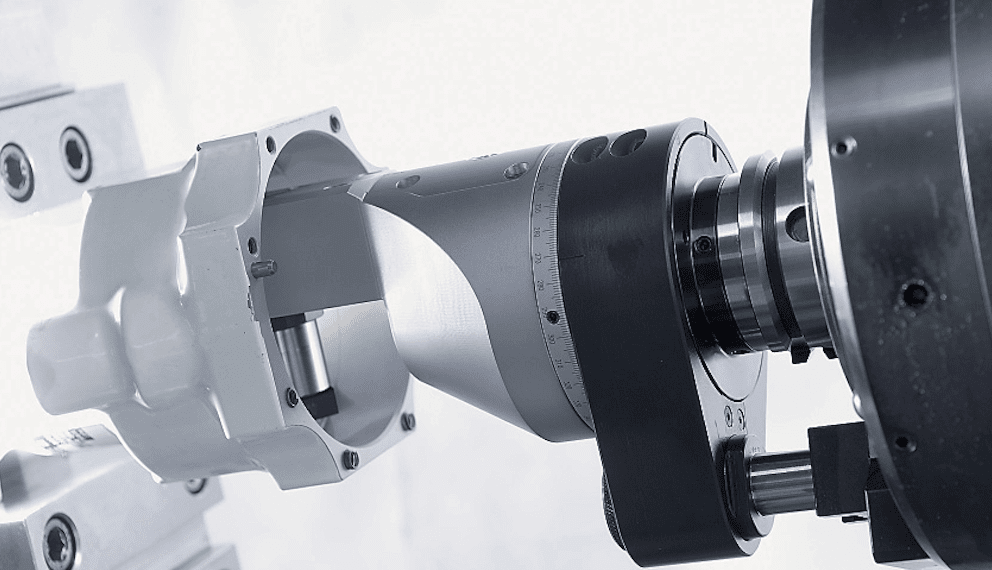

The above said, angle heads are not a simple bolt-on addition or accessory to a 3-axis machine. The initial change will be a postprocessor. The old one will need to be replaced to be able to handle the new calculations. The programming of a job is going to be very different as well. The inclusion of an angle head requires a rewrite of existing programs to accommodate the new tool position and movement. An example can be seen here with just a right-angle drilling approach. Finally, a new feature known as on-machine probing has come into vogue, which is a new element to learn, but it can be very useful in getting to an efficient usage of angle heads in general. While this might seem like a bit of additional investment, time and training, the increase in output options tends to provide more than sufficient rewards for a shop, especially in terms of being able to take on more details and aspects from customers that might have required more expensive setups previously.

Many times, shops considering angle heads are going to choose specific tooling for certain jobs that have sizable return and consistent income flow. This is predictable and well worth the time and planning. The investment can be lucrative when customers realize what’s possible by consistently being produced by a provider creating desired custom parts. A classic example of an angle head with a lot of potential would be a tool that operates in a 90-degree fashion with 360-degree rotational ability, as well as robust rpm speed as well (i.e., 3,000 and 4,000 rpm). Many shop clients find such tools come with various adapters specific to an angle head that gives it changeout capabilities from milling to a tapping unit to drilling and grinding. There are also control features that help lock things in place for a high-pressure application as well as reducing shake.

Some of the complexity of angle heads can be reduced by focusing on tooling that only has one head length versus multiple. Remember, each variation of position represents a library of coordinates to deal with in programming. By working with a fixed head length, it cuts down on some of the variation and makes the programming easier as a result. Shops may find if they go the alternative, they will have to up their game in project programming, particularly in where the center of the tool is in relation to its tip position. Many applications of angle heads have proven the need for macros to account for the variation in head length as a result.

The other factor to keep in mind when using an angle head is that it is fundamentally a spindle component. It doesn’t have the strength or cutting ability that would normally come with more flexible tooling. So, it shouldn’t be used as a deep slicer. Instead, the angle head should be applied with shallower work that has less resistance. Otherwise, a shop is going to be disappointed very quickly by trying to apply a scalpel to something that should be cut with a chainsaw, so to speak.

The last aspect of an angle head to pay attention to involves probing. Probing helps with confirming work stability during a CNC process. While ideally every position and location of a tool head should be planned, scoped and programmed, probing helps cut down on some of this workload, but finding the positions and locations via practical application versus estimation and design alone. That can help speed up new setups tremendously. Angle heads are ideal for this kind of work given their greater range of position not possible with a regular 3-axis approach.